CNN Domestic: AC: "I can tell you that I...was a happy hooker myself."

Length: 5:19

LARGE (62.4 MB) ----- SMALL (6.2 MB)

ANDERSON COOPER: Ruck, maul, blood bin. Just some of the terms used in a wildly popular sport. No, we're not talking about synchronized swimming here. We're talking about rugby. Where the men are tough, the play is rough, and teeth, well, teeth are optional.

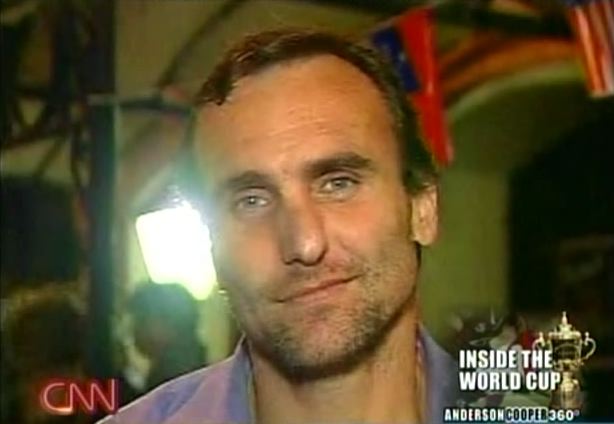

Right now players and fans are swarming France for the World Cup. CNN's Michael Ware is also on hand there. He's not in Baghdad tonight, he's in France to cover the games and to educate me on the fine art of rugby. I spoke to Michael earlier.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

COOPER (on camera): All right, Michael, I got to be honest with you. I don't know anything about this sport. I'm guessing a lot of Americans don't know much about it either. So what is the appeal of rugby?

MICHAEL WARE, CNN CORRESPONDENT: Well, Anderson, the appeal is very much like that of American football. Essentially, it's a violent form of chess. What we have is 15 men on either side, no pads, no helmets, playing on essentially a football-sized field, trying to put the ball across their opposition line, much like scoring a touchdown in the end zone.

One big difference, however, is that in rugby, the game does not stop. Over two 40-minute halves, there's very few stoppages, except for injury. And there's very few substitutions. So much so that in rugby, there's a thing called the blood bin. When someone is injured that badly and they are bleeding that profusely, you're allowed to replace him for 10 minutes to stem the bleeding before he returns to the field. Anderson?

COOPER: And you say that with a smile. You like that, I think.

WARE: Oh, I have many fond memories. It's a fabulous game. And Anderson, this is the World Cup. This is an international game. Twenty international teams fighting it out to be crowned world champions for the next four years.

COOPER: So I know rugby has its own language. I want to go over a couple of the terms with you and if you can tell us what they mean. We are going to put up some pictures, and just telestrate. We're looking at what -- I'm told this over here is a scrum behind this rather large gentleman in the picture. What is a scrum?

WARE: Essentially, Anderson, the scrum is rugby's form of trench warfare. It's one of the ways that you restart the game after there's been an error or a mistake. And what you do is from either side, you take the eight biggest men on the field, put them together in a wedge- like formation, and slam them up against each other and they complete for the ball to get the game going again. Anderson?

COPPER: I'm told what we are looking at now is the haka. What all of these guys are doing. What the heck is a haka?

WARE: The haka is basically a war dance. This is performed primarily by the New Zealand team, known as the All Blacks, but all the Pacific Island teams have a similar version. It dates back to the Polynesian tradition of trying to intimidate your foe prior to tribal warfare. It is simply one of the greatest traditions in international rugby, and it's performed just before the kickoff to scare the living heck out of your opponents.

COOPER: And now the final term is the hooker. This guy, I'm told is the hooker. He doesn't look like any hooker I have ever seen before. What is his job?

WARE: Well, I can tell you that I once in a former lifetime many years ago was a happy hooker myself.

COOPER: Michael Ware was a hooker, wow.

WARE: We talked about the scrum where the two sides just -- absolutely, mate -- where the two sides just pound into each other. It's the hooker who is right in the middle. His arms pinned up against two monstrous guys and both hookers compete for the ball trying to win it for their team using nothing but their feet to literally hook the ball back to their side.

COOPER: OK, now Michael, I know you referenced your own rugby history. You were a happy hooker. I wonder if we can show a picture of you close up. I want to ask, is this the result of playing rugby? There seems to be -- your nose goes in a couple of directions. I'm wondering, is that from rugby?

WARE: Absolutely, Anderson. And if you wanted me to, my nose has been broken so many times -- I lost count at 10 or 11 -- I can break it for you right now here on TV, so fluid and malleable is it. This is the essence of rugby. It's about a physical contest. When it's played well, truly is a hard man's game. You got to love it, Anderson.

COOPER: I understand it looks like, there are soccer hooligans who follow around these teams. Obviously there's a lot of rugby fans. You're at a bar tonight. It seems like beer and rugby kind of go together?

WARE: Absolutely, hand in hand. One does not go without the other. It also is part of the culture of the game. Once you take the field and you belt into each other, it's one of the greatest honors afterwards to stop and have a beer with your opposite number. And that's shared by the supporters.

I mean, rugby is followed by an international tribe, and here in Marseilles in the south of France, there is four teams competing out of the eight left trying to be world champions. And all their followers have descended. And Marseilles tonight is one huge drunken spectacle, full of color and noise, Anderson.

COOPER: All right, well, go join it. Michael Ware, appreciate it. Thanks, Michael.

WARE: Thank you, Anderson.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

COOPER: I have always wondered about the nose. You've got to ask.