THE AUSTRALIAN: From Front Line to Front Row [Interviewed at Australian Fashion Week]

By MARION HUME

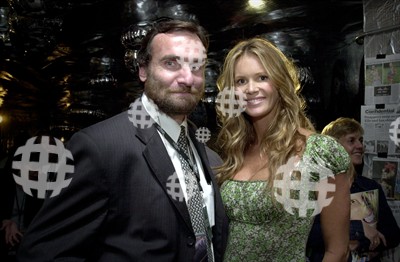

MAY 8, 2002 : Former model turned actor Elle Macpherson with Time Magazine journalist Michael Ware

in Sydney 08/05/02 during Australian Fashion Week.

LAST week, Michael Ware went to some fashion shows. A month ago, the Time magazine foreign correspondent was undercover in former Taliban strongholds in southern Afghanistan, where clothes had the power to save his life. He accepted The Australian's invitation to come to Fashion Week out of curiosity.

"It intrigued me. I'm a foreign correspondent and fashion is a world that is obviously very foreign to me," says Ware. "I've always had a preconceived notion of the fashion industry. Can it be as empty as it really appears? I wanted to compare it [with] the places I go and the things I see.

"The first thing that struck me was that the accreditation badges [delegates wear around their necks] are strikingly similar to the one I wore at all times in East Timor. My identity card looked like this one [for Bar Bazaar]. But it didn't say `Be famous, Be someone, Be seen.' That's a treat."

Colour? "It can save your life. In a combat situation, decisions are made on the split second. That first glimpse can be a defining moment. Take Timor. There, the Indonesian military-backed militia wore red-and-white headbands and armbands, and a sight of that and you knew you were approaching a dangerous situation,'' he says.

"Alternatively, in Afghanistan the signature turban of the Taliban is of a particular kind of dark black silky cloth, which is much longer and so much puffier than other turbans. As soon as you see one, you automatically know, even if he's not Taliban, then he is not far away from it, so it's a dangerous situation.

"I ended up adopting Afghan dress once I had grown my beard. I studied what the Afghan men wore and how they wore it, and it helped me to be able to stay alive. Sometimes the gun can't protect you. What can is looking like everyone else."

At Fashion Week, Ware bristled when he spotted stylist Kelvin Harries dressed in a boy scout-military-looking shirt.

"My eye was immediately drawn across the crowd. You become acutely aware of uniforms in my world because they can signal change in a situation, either making it more friendly or more dangerous. I had to catch myself, tell myself there was no reason to worry.

"A uniform can have dire consequences. Here it represents benign authority and security. But for others it is not a fashion statement.

"The single most disconcerting thing that I experienced at Fashion Week was the really gaunt looks on some of the model's faces. That emotional blankness had a resonance for me. It compared to what we call the thousand-yard stare, when people who have been through terrible situations look straight through you. The look on some of these models had that vacancy.

"I know it is passe, but the dire emaciation of these women conjures immediate associations for me or anyone else who has ever been to a refugee camp. The only other people I have seen like this have been struggling to live. I don't want to be overly judgmental but it does make me angry. I think we've got no right to make ourselves this thin.

"I don't want to be hypercritical. But the fluff and the pap that goes with all this! It is decadent, frivolous and vacuous. I've listened in to conversations and they seemed to me to lack a sense of proportion. But then I reminded myself we are in Sydney, Australia, in the Western world.

"But it could get too much. One of the photographers working this week was an old shooter mate of mine from East Timor. Then the next minute I was literally standing next to Elle Macpherson. I had to go outside and have a couple of cigarettes just to help myself come to terms with the unreality of it."

At the shows, Ware was noticeably jumpy. Sitting next to him at the Grand Marnier 5 show, I was aware his body was moving the whole time.

"I tried to concentrate on sitting still. I felt self-conscious. The other reason is going to sound a bit prudish, but the visible breasts made me really uncomfortable. When I got back from Afghanistan, I had gone four months without hardly seeing a woman, except for a few in the burka. South Afghanistan is a conservative stronghold, so when I came home, for the first 10 days I had trouble coping, not just with crowds but with displays of flesh.

"I didn't know where to look. How my Afghan friends would have reacted was playing through my mind as well. They would have been salivating.

"They are 25, 30-year-olds who have never had sex with a woman.

"We talked about everything, from Islam to weaponry.

"But when it came to sex, they would ask the most simple things. But then, even those who were married might have had 13-year-old brides they had never seen naked.

"Discarded Western magazines would turn up at the American air base and you were free to help yourself. I saw a US Vogue and I took it into town and there was an obsession about it. The guys loved it. It got to the point that that magazine was kept in my room and one of the Afghans elected himself as its guardian -- he called himself the librarian -- and he would note who was taking it out and when it would be returned. When I left Kandahar it was the first possession they grabbed.

"The ones who could read English were studiously poring over the text and they would ask, 'What is that?', 'Who would buy that kind of thing?', 'How much does it cost?', 'Would you go to the bazaar to get it?' and I would explain about boutiques. But they could never understand why these women would shame themselves so much.

"I live with my girlfriend at Bondi Beach. A beach is hard to explain to people in a landlocked country. They'd say, 'What do people wear?' and I would describe a bikini and a one-piece, and after the titillation factor I would get very serious questions: 'Do you take your woman to this place?', 'So other men can see your woman in these clothes?' On two separate occasions, men asked me, 'How do you resist the urge to want to kill those men?'

"To put this in context, one of my friends lives with his mother, father, uncles, cousins. His male cousin is his best friend. He can't even talk to his female cousin. If he did, his uncle would be honour-bound to take retribution, either flogging, humiliation, even death. It is about the avoidance of sin. To avoid sin, you avoid the temptations that lead to sin.

"Something else at the shows took me back to the war zone, although on a totally different scale. Getting in is a bit like passing a checkpoint. In my world, when they say no, they mean no. The authority comes from the gun. You have to do everything in your means to either bluff, bullshit, bribe or avoid to get to where you want to go and I had precisely that experience at Morrissey.

"The place was packed, it was a long way to get through the approved channel, so we went through a gate, through the technical area and, at just the right moment, we popped out and the show started. I thought, this is exactly what I do all the time.

"I have respect for fashion journalists. Not for the life of me could I put up with this circus. When I've spent five days travelling to a place that is extraordinarily difficult to get to, at much risk, to get an interview and a fashion story gets in instead, well, I understand the reader has only a certain stamina for what I do.

"Put it this way, you come really quickly to an understanding of what things really are worth dying for. Sometimes it was just water off a duck's back. But sometimes it made me want to go up and shake someone. It just reminds me of the privileged state we live in.

"It has taken me quite some mental effort to come to terms with some of the events here in the [past] few days. People say: 'It's good to see you in the real world' but this isn't the real world. Fashion is very much the unreal world.

"Yet it's part of life. It's not something we should completely denigrate and refuse to give any concentration to at all. We should just not be exulting it beyond its proper context. Fashion Week to me has been a fun experience. What's great is that what I see at a fashion show is not going to live with me late at night.

"At the same time, it is a little depressing. I've gone home after these extravaganzas each night trying to put the pieces back together. In conflict situations, while they are never black and white, you feel you know what's right and what's wrong. Here, there's a nagging guilt. This has been an emotional experience for me. I'm really glad I've been here and I've had an insight into what, to me, is a different universe. But it has been a very up-and-down ride."